“J. Crew Likely to File for Bankruptcy in Virus’s First Big Retail Casualty - The New York Times” plus 3 more |

- J. Crew Likely to File for Bankruptcy in Virus’s First Big Retail Casualty - The New York Times

- J. Crew likely to file for bankruptcy in first big retail casualty of coronavirus - Hartford Courant

- Standing by in sports, Sun. May 3 - Detroit Lakes Tribune

- We Are Losing a Generation of Civil-Rights Memories - The Atlantic

| J. Crew Likely to File for Bankruptcy in Virus’s First Big Retail Casualty - The New York Times Posted: 03 May 2020 08:21 PM PDT  J. Crew, the mass-market clothing company whose preppy-with-a-twist products were worn by Michelle Obama and appeared at New York Fashion Week, is expected to file for bankruptcy protection as soon as Monday. It would be the first major retailer to fall during the coronavirus pandemic, though other big industry names including Neiman Marcus and J.C. Penney are likewise struggling with the devastating toll of mass shutdowns. J. Crew has been in negotiations with lenders on how to handle its debts for weeks, according to two people with knowledge of the situation, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because discussions were confidential. The retailer's board was expected to confer on Sunday evening and J. Crew could file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection as soon as Monday, the people said. The company on Sunday declined to comment. The pandemic has been disastrous for the already weakened retail industry. In March, sales of clothing and accessories fell by more than half. The numbers for April are expected to only be worse, because many stores were open for at least some of March (e-commerce, a relatively small contributor to total sales for most store chains, is not enough to make up for the closures). Retailers have furloughed employees, slashed executive salaries and hoarded cash in a desperate attempt to survive until the shutdowns are lifted. And there is widespread acknowledgment that J. Crew, which also owns the popular millennial denim brand Madewell, is not likely to be the only retailer to face the brink. J. Crew was carrying a debt burden of $1.7 billion based on a leveraged buyout in 2011 by two private-equity firms — TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners — even before the coronavirus brought clothing sales to a near-halt in the 182 stores, 140 Madewells and 170 outlets it was running as of early March. And it had struggled to adapt to changing consumer tastes. But in recent months it seemed to be making strides toward a more viable future. The company recently hired a new chief executive and was planning an initial public offering of Madewell this spring in order to pay down some of the debt and rehabilitate the J. Crew brand. The coronavirus scuttled those plans and eventually toppled the company. J. Crew started life in 1947 as a family-run low-priced clothing line for women called Popular Club Plan, and in 1983 it was renamed and reinvented as a catalog company selling turtleneck tops and crewneck sweaters in "Preppy Handbook" shades. It made the leap to household name and 21st century fashion fairy tale in late October 2008 when Mrs. Obama, whose husband was then the Democratic candidate for president, appeared on "The Tonight Show With Jay Leno." This was just days after it had been revealed that Sarah Palin, the Republican candidate for vice president, had been given a costly wardrobe makeover by her party. "I want to ask you about your wardrobe," Mr. Leno said to Mrs. Obama. "I'm guessing about 60 grand? Sixty, 70 thousand for that outfit?" "Actually, this is a J. Crew ensemble," Mrs. Obama replied, referring to her $148 yellow pencil skirt, $148 yellow and brown print tank top and $118 matching yellow cardigan. "Ladies, we know J. Crew. You can get some good stuff online!" It was a priceless marketing moment. After that, everyone knew J. Crew, which seemed to embody the high/low mix-and-match trend of the moment. The company was purchased by TPG in 1997 in a leveraged buyout from the founding Cinader family, and was taken public in 2003 — only to be reacquired for approximately $3 billion by TPG and Leonard Green & Partners nearly a decade ago. Its creative director, Jenna Lyons, who had first joined as part of the design team in 1990, became a boldface name, known for her black-rimmed glasses, gangly frame and love of sequins and camouflage. Newspaper reports crowed about the comeback of the company's chief executive, Millard S. Drexler, who had previously led Gap Inc. for years. Mr. Drexler, who goes by Mickey, became famous for riding his bicycle around the office and checking in with store associates via speakerphone. In 2011 J. Crew became the first mass-market accessible brand to breach the high fashion parapet and present at New York Fashion Week. Vogue crowned the brand "a significant voice in the conversation on American style." As the face of the brand, Ms. Lyons attended the Met Gala and, in 2014, played a role on the HBO show "Girls." In 2017, however, after two years of falling sales, Ms. Lyons left the company. J. Crew, the criticism went, had gone too fashion, falling into the trap of prizing quirk over quality and pricing itself out of practicality. And it had never focused enough on e-commerce. Madewell, its younger, simpler — "more authentic" — sister brand, acquired by Mr. Drexler in 2006, was the company's new shining star. Indeed, after Ms. Lyons left, Madewell's designer, Somsack Sikhounmuong, who had switched over to J. Crew in 2015, took the top creative spot. Much was made of a return to core values. It was too little, too late. For a fashion brand to thrive it must be either needed or wanted. J. Crew, sitting somewhere in the netherland of style and price, was neither. A few months after Ms. Lyons's departure, Mr. Drexler stepped down and two months later, Mr. Sikhounmuong left, starting a round robin of executives and designers. That served ultimately to confuse rather than clarify the identity of the company and its strategy. Jan Singer, formerly of Nike and Victoria's Secret, was named as J. Crew's newest leader in January. Madewell, which filed for an I.P.O. in the fall, was expected to go public this spring while J. Crew remained private, but those plans were ultimately scrapped in March, which added a new wave of pressure and question marks to J. Crew's future. Now the question is whether the upheaval of the retail industry — which predates the pandemic, with the collapse of Barneys New York late last year — will continue. "The companies going into bankruptcy, for the most part, were companies that were struggling before Covid — we have not seen true Covid-only bankruptcies," said James Van Horn, a partner at the law firm Barnes & Thornburg and a specialist in retail bankruptcy. However, he added, "depending on how the current situation continues, that may change." For instance, Brooks Brothers, another quintessential American shopping institution, is already facing questions about its future. "In the ordinary course of business, Brooks Brothers consistently explores various strategic options to position the company for growth and success, in partnership with its financial advisers at P.J. Solomon," a spokesman said, in response to question about a potential sale. |

| J. Crew likely to file for bankruptcy in first big retail casualty of coronavirus - Hartford Courant Posted: 03 May 2020 07:37 PM PDT  In 2017, however, after two years of falling sales, Lyons left the company. J. Crew, the criticism went, had gone too fashion, falling into the trap of prizing quirk over quality and pricing itself out of practicality. And it had never focused enough on e-commerce. Madewell, its younger, simpler — "more authentic" — sister brand, acquired by Drexler in 2006, was the company's new shining star. Indeed, after Lyons left, Madewell's designer, Somsack Sikhounmuong, who had switched over to J. Crew in 2015, took the top creative spot. Much was made of a return to core values. |

| Standing by in sports, Sun. May 3 - Detroit Lakes Tribune Posted: 03 May 2020 04:00 AM PDT Dr. Arden Beachy was recently featured by the Forum of Fargo Moorhead's Jeff Kolpack after testing positive for COVID-19 and subsequently recovering. Beachy, a physician and emergency room doctor at Lakewood Health System in Staples, was a standout quarterback for the Staples-Motley Cardinals and later North Dakota State University. Beachy closed out the Bison's run at Dacotah Field in 1992 and was the starting quarterback the inaugural year of the Fargodome the following year.  Dr. Arden Beachy NDSU was 9-1 in the regular season in 1992, with the only loss coming at St. Cloud State's Homecoming when former Laker kicker Ludvig Millfors' game-winning field goal attempt missed wide by inches. I was in attendance as a third-year student at SCSU and watched that game with Mark Nelson, a tailback at Staples who I played against all through high school, along with Beachy. My 1988-89 Lakers were the first team to be under head coach Rick Manke since we were freshmen and changed the course of DL football winning the first 10 games before a section final loss ended the campaign. No. 10 Detroit Lakes and No. 4 Staples-Motley had two memorable matchups. Both teams were undefeated going into week seven, Homecoming in Staples. The Cardinals' field was crammed with fans in one of the biggest matchups of the year in outstate football. Tribune Sports Editor Ralph Anderson labeled it "The Game" in his preview that week. Beachy, fullback Darren Gorder and the speedy Nelson duked it out with the Lakers, led by Craig Thielen at quarterback and the punishing backfield duo of Chris Fossen and Jay Grasto running behind an experienced and effective senior-heavy offensive line. DL prevailed 41-22 taking a lead into halftime on a trick passing play before securing the victory when Manke's adept play calling engineered a drive of all running plays that ate up the entire third quarter clock. Beachy and the Cardinals exacted revenge in the section final at Mollberg Field 33-7, a disappointing end for the Lakers in the year that the field was dedicated to Del Mollberg. Staples-Motley went on to finish second in the state falling 35-28 to Lakeville at the Metrodome. The 10-1 DL season was a showcase of what Manke had brought to the program and the state championships that were soon to come. The 10 wins were more than the prior two seasons, a 5-5 run in 1987 and a 4-5 season in 1986. Throughout the 1980's, the 1981 team was the only other club to win more than five games (6-5) in a season. Beachy's football and track career came to an abrupt end after a MCL and ACL tear against Pittsburgh State in 1993. He remained on the team to mentor quarterbacks Rob Hyland and Mike Gidley before completing his medical studies. Nelson and I met at the mailboxes of Sherburne Hall at SCSU the first day of college. I looked at him and said, "Hey, you're the nerd!" Mark rocked the black-rimmed glasses under his football helmet in high school and we had given him the nerd moniker on the field. I ended up being the best man at Nelson's wedding in Phoenix a few years later completing a total flip from sworn enemies on the gridiron to best friends. It's a small world.  Braydon Ortloff Ortloff, Yliniemi, Doppler up for MSUM awards Three former Lakers are up for awards at Minnesota State University Moorhead after impressive seasons with the Dragons. Ortloff (wrestling) is one of five athletes nominated by their coaches for male athlete of the year. Ortloff was featured in the Tribune in early April after qualifying for the NCAA Division II National Championships. Doppler (volleyball) and Yliniemi (diving) received nominations based on student-athletes in their first year of competition (freshman or transfer students) that have made the most impact on their sport. They are nominated by their head coach.  Lexi Yliniemi Yliniemi earned a trip to the NCAA Division II national pre-qualifying meet on day two of the Northern Sun Intercollegiate Conference Championships at the BSC Aquatic and Wellness Center in Bismarck, N.D. She was also the athlete of the week Jan. 20-26 after winning the 3-meter diving competition at the Dragons' home quadrangular, her second victory of the season, and adding a third-place finish on the 1-meter board.  Teeya Doppler Doppler appeared in 27 matches recording with 125 kills and 53 blocks. She had a career-high 12 kills in a loss to Sioux Falls in November. She and former Laker and MSUM wide receiver Jake Richter garnered athlete of the week honors Nov. 4-10.  Bruce Paskey (2), captain of the Detroit Lakes high school baseball team, crosses home plate with the first Laker run in a 9-2 victory over Fergus Falls. Harry Hotchkiss is the Fergus Falls catcher. Terry Knauf is the umpire behind the dish. Photo by Ken Prentice MISCELLANY Fifty years ago this week in 1970, the Detroit Lakes varsity baseball team got off to a 4-0 start to the season. Pitcher and captain Bruce Paskey hit a two-run homer in the sixth inning to snap a 3-3 tie to give the Lakers a 5-3 victory over Park Rapids at the wind-blown senior high school baseball field. Mike Metelak scored three of the DL runs. Paskey fanned nine batters and allowed only four hits, retiring the side in three of the last six innings. The day prior, DL took advantage of five Fergus Falls errors scoring nine runs in six innings to down the Otters 9-2. Rocky Chrastil earned the victory going four innings, striking out five. Doubles by Brian McLeod and Jim Rolfe brought home the eventual winning runs in a three-run Laker second. |

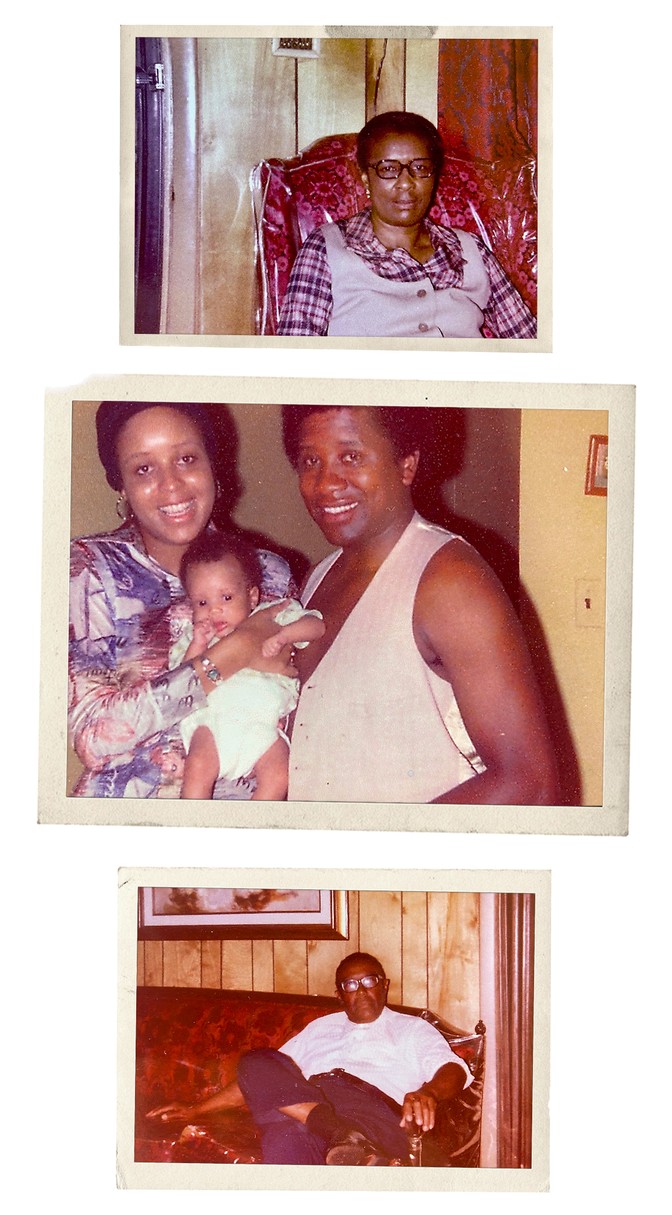

| We Are Losing a Generation of Civil-Rights Memories - The Atlantic Posted: 03 May 2020 03:16 AM PDT  I knew it was only a matter of time before coronavirus deaths hit my social-media feeds—before people I knew would grieve, or even become ill and die themselves—but I wasn't prepared for the speed or relentlessness with which it happened. Or that most of the victims I'd see would be black. I knew that to a large extent this reflected the people and topics I followed, but it was something bigger too, a hint of the grim reality that was only just emerging. My eyes began to search for COVID-19 in every death announcement. It wasn't always there, as with the Reverend Joseph Lowery, known as the "Dean of the Civil-Rights Movement," who died on March 27 at the age of 98, of causes unrelated to the coronavirus. But it often was, and as I scrolled past smiling photos of people of all ages—daughters, sons, cousins, matriarchs, and patriarchs—I wondered how American society would bear a loss of this magnitude, what it would do to our country to lose them and all they remembered. Bree Newsome: The Civil-Rights Movement's generation gap I've been thinking about ancestral memories for a long time. In the mid-'80s, when I was 11, I interviewed my grandparents. For all the time I'd spent with them over the years—every day after school, plus all summer while my mom worked—I realized I knew little about their early lives and the stories of their families. Once in a while, they'd let slip little anecdotes—some amusing, others revealing of the discrimination they had endured during the brutal Jim Crow era. But much of their lives lay behind a heavy curtain that rarely opened. They didn't like talking about the past, and if their conversation touched on it, they didn't linger there. As I slouched cross-legged on the variegated shag carpet in their Memphis bungalow, Grandma—a tall, lean, reddish-brown woman in her 70s—sat languid and elegant on a tufted gold velvet armchair, its plastic upholstery cover crinkling beneath her when she shifted. A few feet away, Granddaddy, a round man in his 80s with horn-rimmed glasses resting on his dark bronze face, perched on a red velvet damask armchair, also covered in plastic. They gazed at nothing in particular—nothing visible to me, anyway—while I formed my questions: What were the names of the Mississippi Delta towns where they were born? What were the names of their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents? What were the oldest tales they could recall?  They answered in turn, hesitantly at first, noting dates and surnames, mentioning towns, states, and even another country, Cuba, through which Granddaddy's ancestors passed before landing in the American South. I scribbled notes in pencil on a scrap of newspaper, the only paper I had handy. This would be our only interview, extracting mostly biographical particulars. I took home the scrap of paper bearing my notes and put it in a desk drawer, where it lay for years among a jumble of trinkets and ephemera before disappearing in the whirlwind of packing for college. Over the course of my burgeoning adulthood, I gradually became aware of its loss, my heart dropping when something triggered a memory that took me back to its precious details. Never again, I swore, would I fail as the custodian of a fragment of history. But I did fail again—this time with my father, whose stories I ceded to the forgetfulness of time until I was well into adulthood. Like my grandparents, he is from Jim Crow Mississippi, and though he was born a generation later—in 1944—little had changed with regard to racial oppression. In 1968, before I was born, he was a Memphis police officer whose undercover work brought him to the Lorraine Motel minutes before an assassin's bullet struck Martin Luther King Jr. A well-known photograph captured my father kneeling over King while attempting to render first aid, as three people standing nearby point in the direction from which the shot came. I grew up knowing little of these events beyond my father's presence in the photograph; he never discussed them, and the rest of my family barely mentioned them. Over time, I'd discover conspiracy theories about his appearance at the scene of King's murder. Read: The last march of Martin Luther King Jr. I used to attribute my reluctance to explore his past to my fear of discovering any truth to the conspiracy theories. But underlying that was a more fundamental fear, prefigured by my grandparents' reticence and my lost notes: that of the certain horror and grief I'd have to engage with, regardless of the specifics I uncovered. Avoiding my father's story hadn't shielded me from the anguish I dreaded, which already inhabited me in some hidden place near the edge of perception. Rather, it merely allowed more history to be lost. And lost history, I came to understand, was far more than a personal concern—it represented a danger to the hard-won gains my forebears and so many like them had made against racial apartheid and atrocities. The matter is more urgent now than ever, as the coronavirus ravages the populace and the U.S. response threatens to repeat ugly historical episodes. But to recognize this, you'd need to know the stories of our elders, understand the world through their eyes. Then you'd see that what once appeared to many as inevitable social progress accompanying our advance through the decades was in fact fragile and contingent—and, without constant vigilance, forfeited. Read: How the pandemic will end This is evident in the actions of Donald Trump, who has defended his use of the racist terms Chinese virus and Wuhan virus, and whose administration has made little to no provision for the health of the more than 170,000 people held by the Federal Bureau of Prisons—a disproportionately black population—or the tens of thousands of immigrants in federal detention. His words and actions echo prevailing social and scientific narratives to which my grandparents and father were subject, those that painted black people as disease vectors and even facilitated infections, as in the decades-long Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Even as Trump acknowledged with seeming concern the mounting evidence that black people face much higher rates of severe illness and death from COVID-19 than other racial groups, he wondered aloud, "Why is it that the African American community is so much, numerous times more than everybody else?" The answer is no mystery to Jim Crow survivors, witnesses to America's long legacy of disinvestment in and devaluation of black people; it's as simple, and complicated, as this country's racist underpinnings. In the fall of 2015, I finally interviewed my dad—and this time, I made an audio recording. Five years later, we're still interviewing and recording. In that time, I've heard stories that racked me with weeping and others that swelled me with pride. But most of all, they've enriched my understanding of this moment we live in now—how we got here and the precariousness of our position. As we face down the unthinkable horror and grief of this pandemic, I'm grateful for the opportunity to preserve and share a fragment of our collective history, particularly at a time when our fundamental rights—if not our very lives—are threatened as much by ahistorical perspectives as by invidious intent. This story is part of the project "The Battle for the Constitution," in partnership with the National Constitution Center. We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com. Leta McCollough Seletzky is an essayist and memoirist based in Walnut Creek, California. She is the author of the forthcoming book The Kneeling Man. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "black rimmed glasses" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

0 Yorumlar